Lesson 2: Processing a Form Submission

So you've completed Lesson 1 and you're saying to yourself, "ok, but how do I make this page actually do something?"

This tutorial will guide you through setting up a simple form that can be used to update some information in the database. For simplicity we will use a contrived example - updating the title for every user who belongs to a particular group. However, the general pattern can be applied to any aspect of your data model.

Creating the Form

To begin, we will create a new page that will contain the form itself. Creating a page is covered in Lesson 1, so please go through that tutorial first.

With all of our routes, you may notice that index.php could easily get to be quite long. To help break the code into more manageable chunks, we'll factor out our code into controller classes, with each class in a separate file. In userfrosting/controllers/GroupController.php, we'll create a method pageGroupTitles:

{% raw %}

public function pageGroupTitles(){

// Access-controlled resource

if (!$this->_app->user->checkAccess('uri_group_titles')){

$this->_app->notFound();

}

// Get a list of all groups

$groups = GroupLoader::fetchAll();

$this->_app->render('group-titles.html', [

'page' => [

'author' => $this->_app->site->author,

'title' => "Update Group Titles",

'description' => "Update the title for every user in a particular group",

'alerts' => $this->_app->alerts->getAndClearMessages()

],

"groups" => $groups

]);

}

{% endraw %}We'll also create the form template file, group-titles.html:

{% raw %}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

{% include 'components/head.html' %}

<body>

<div id="wrapper">

{% include 'components/nav-account.html' %}

<div id="page-wrapper">

{% include 'components/alerts.html' %}

<div class="row">

<div class="col-lg-6">

<div class="panel panel-primary">

<div class="panel-heading">

<h3 class="panel-title"><i class="fa fa-users"></i> Change Group Titles</h3>

</div>

<div class="panel-body">

<form class="form-horizontal" role="form" name="titles" action="{{site.uri.public}}/groups/titles" method="post">

{% include 'common/components/csrf.html' %}

<div class="form-group">

<label for="input_group" class="col-sm-4 control-label">Primary group</label>

<div class="col-sm-8">

<select id="input_group" class="form-control select2" name="group_id">

{% for id, group in groups %}

<option value="{{id}}">{{group.name}}</option>

{% endfor %}

</select>

</div>

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<label for="input_title" class="col-sm-4 control-label">New Title</label>

<div class="col-sm-8">

<input type="text" id="input_title" class="form-control" name="title" placeholder="Please choose a new title">

<p class="help-block">This will become the new title for all users in the selected group.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="form-group text-center">

<button type="submit" class="btn btn-success text-center">Update Titles</button>

</div>

</form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

{% include 'components/footer.html' %}

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

{% endraw %}Nothing too fancy here. We're creating a form with the name titles, and giving it two fields: a <select> control, for choosing the group name, and a text input, for specifying the new title that will be given to all primary members of the selected group.

You'll notice that we have the form POST to the exact same URL as the URL of the page itself. How can we do this? Well, it turns out that an HTTP request consists not just of a URL, but an HTTP method as well. Thus, making a GET request from http://example.com/groups/titles is different from making a POST request to http://example.com/groups/titles.

Slim can detect the difference between these two requests, and actually treats them as separate routes! Thus, we can have:

{% raw %}

$app->get('/groups/titles/?', function () use ($app) {

// Do what we need to do to render the page containing the form in the GET route

});

{% endraw %}and also

{% raw %}

$app->post('/groups/titles/?', function () use ($app) {

// Process the form submission in the POST route

});

{% endraw %}Note the difference between $app->get(... and $app->post(....

That answers the how, but what about the why? To answer this, we must understand the principles of REST:

RESTful systems typically, but not always, communicate over the Hypertext Transfer Protocol with the same HTTP verbs (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc.) which web browsers use to retrieve web pages and to send data to remote servers. REST interfaces usually involve collections of resources with identifiers, for example

/people/paul, which can be operated upon using standard verbs, such asDELETE /people/paul.

The keywords here are resources and verbs. Semantically, we are to understand URLs as representing abstract resources. In this case, we might want to think of /groups/titles as a resource representing something like "a service for setting a common title for every member of any given group".

Thus, GETting that resource gives us an HTML page containing a form that we can fill out to interact with that service. POSTing to that resource, on the other hand, actually invokes the service with the parameters specified by the filled-out form.

Ok, enough about REST. Let's go back to index.php, and invoke our controller method pageGroupTitles in our GET route:

{% raw %}

$app->get('/groups/titles/?', function () use ($app) {

$controller = new UF\GroupController($app);

return $controller->pageGroupTitles();

});

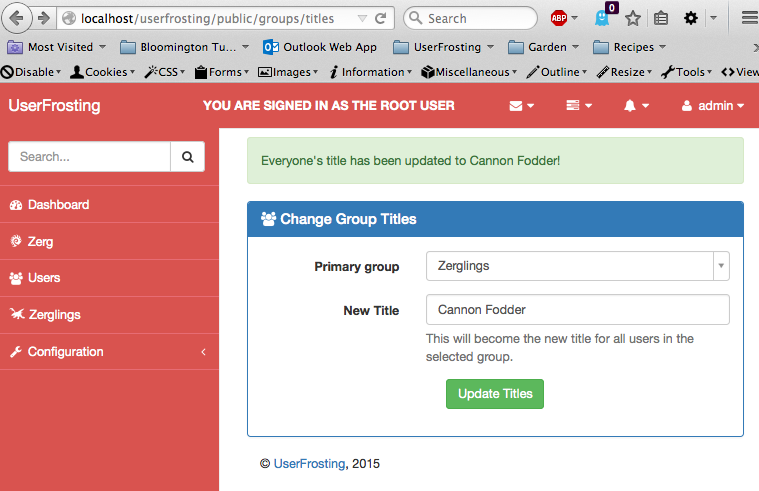

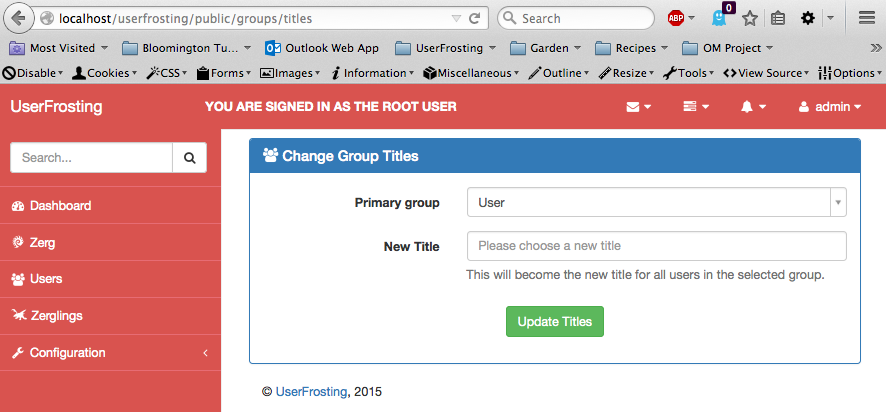

{% endraw %}And then we should be able to visit groups/titles:

Processing the Submitted Form

Alright, we now have a page that contains a form that will POST to /groups/titles. Let's set up our POST route:

{% raw %}

$app->post('/groups/titles/?', function () use ($app) {

$controller = new UF\GroupController($app);

return $controller->updateGroupTitles();

});

{% endraw %}Where updateGroupTitles is a method that we will define, again in the GroupController class:

{% raw %}

public function updateGroupTitles(){

...

}

{% endraw %}Authorization (Access Control)

Just like in the GET route, we need to check that the client actually has permission to perform the POST request. In some situations, we might want a more fine-grained approach to authorization, where access is granted or denied depending on the contents of the fields that are submitted. For example, in the "update user" resource, users may be allowed to update some user fields but not others.

For simplicity, in this case we wil use a single authorization hook to control access to the entire route. To make things even simpler, we will use the same authorization hook for POSTing to this resource as we do for GETting from it:

{% raw %}

public function updateGroupTitles(){

// Access-controlled resource

if (!$this->_app->user->checkAccess('uri_group_titles')){

$this->_app->notFound();

}

...

}

{% endraw %}Validating the Submitted Input

The next thing we need to do is validate the input. After all, the cardinal rule of web development is to never trust user input! If we don't validate the input, we potentially leave ourselves vulnerable to all sorts of security and usability hazards.

First, we retrieve the POSTed data:

$post = $this->_app->request->post();

Now, $post contains the raw request data, which is basically equivalent to PHP's $_POST array. To validate the data, we can either go through and check each field in the code, or we can use Fortress to automatically validate the data against a WDVSS request schema. The request schema allows us to apply some common validation rules as defined in the WDVSS standard. In practice, you will often be able to perform simple, syntactic validation (numeric ranges, string lengths, etc) with a request schema, but will need to hand-code more complex database-driven validation (checking that a username is not in use, validating a security token, etc).

Let's create a simple WDVSS request schema, written as a JSON document, for our form:

/schema/forms/group-titles.json

{% raw %}

{

"group_id" : {

"validators" : {

"integer" : {

"message" : "group_id must be an integer."

}

},

"sanitizers" : {

"raw" : ""

}

},

"title" : {

"validators" : {

"length" : {

"min" : 1,

"max" : 150,

"message" : "The new title must be between 1 and 150 characters long."

}

},

"sanitizers" : {

"raw" : ""

}

}

}

{% endraw %}Note that the two top-level keys in this JSON document, group_id and title, match the names of the fields in our form. For each field we can define one or more validation rule, along with some parameters. We can also define a sanitization protocol. In most cases, we actually don't want to sanitize the input before using it, so we set the sanitizer to raw.

The schema also acts as a whitelist. Fortress will ignore any submitted fields that do not match the name of a field in the request schema. This is useful, for example, if we intend to pass the entire array of form data on to some other function, and we want to be sure that no (potentially malicious) data has been snuck into the request.

Ok, so now we can actually use our schema along with Fortress in our controller code:

{% raw %}

public function updateGroupTitles(){

// Access-controlled resource

if (!$this->_app->user->checkAccess('uri_group_titles')){

$this->_app->notFound();

}

// Fetch the POSTed data

$post = $this->_app->request->post();

// Load the request schema

$requestSchema = new \Fortress\RequestSchema($this->_app->config('schema.path') . "/forms/group-titles.json");

// Get the alert message stream

$ms = $this->_app->alerts;

// Set up Fortress to process the request

$rf = new \Fortress\HTTPRequestFortress($ms, $requestSchema, $post);

// Sanitize

$rf->sanitize();

// Validate, and halt on validation errors.

if (!$rf->validate()) {

$this->_app->halt(400);

}

// Get the filtered data

$data = $rf->data();

...

}

{% endraw %}Notice that we pass three things to HTTPRequestFortress: the request schema, the POSTed data, and a message stream where Fortress can place any error messages generated during validation.

We then call sanitize, which whitelists the POSTed data. validate applies our validation rules as defined in the schema, returning false if any validation rule was failed.

If we are processing this form submission via AJAX, and we encounter an error during validation, we can simply halt the request and return an HTTP 400 error code. Otherwise, we would need to redirect the request back to the original page containing the form - but more on this later.

Oh yeah, there's one more thing! There's actually one more field that gets submitted in every form - the CSRF token. This gets checked by the CSRF middleware, so we don't need to worry about it here. Fortress will, by default, automatically filter it out in the filtered data array, since it is not declared in the request schema.

Interacting with the Data Model

Ok, so now we have a validated, clean group_id and title. The next thing to do is actually interact with the data model, which will let us update the titles for each user in the database.

The data model allows us to interact with the database via database objects, which are object-oriented representations of records in the database. I'll do a more in-depth tutorial on the data model later; for now, just follow along with what I'm doing here.

The MySqlUserLoader class (aliased as simply UserLoader) is a static class that lets us fetch one or more User objects from the database. We can use the fetchAll method to fetch an array of Users, and even filter by some criteria. For example,

$users = UserLoader::fetchAll($post['group_id'], "primary_group_id");

will give us an array of all users whose primary group is $post['group_id'].

Then, we can simply cycle through this array of users, and set their titles to the new value:

{% raw %}

foreach ($users as $user_id => $user){

$user->title = $post['title'];

$user->store();

}

{% endraw %}Behind the scenes, invoking $user->title takes advantage of PHP's magic methods to let us get and set the various fields for the database object. Calling the store() method then commits the modified User back to the database.

Ok, so let's put the entire route method together:

{% raw %}

public function updateGroupTitles(){

// Access-controlled resource

if (!$this->_app->user->checkAccess('uri_group_titles')){

$this->_app->notFound();

}

// Fetch the POSTed data

$post = $this->_app->request->post();

// Load the request schema

$requestSchema = new \Fortress\RequestSchema($this->_app->config('schema.path') . "/forms/group-titles.json");

// Get the alert message stream

$ms = $this->_app->alerts;

// Set up Fortress to process the request

$rf = new \Fortress\HTTPRequestFortress($ms, $requestSchema, $post);

// Sanitize

$rf->sanitize();

// Validate, and halt on validation errors.

if (!$rf->validate()) {

$this->_app->halt(400);

}

// Get the filtered data

$data = $rf->data();

// Load all users whose primary group matches the requested group

$users = UserLoader::fetchAll($post['group_id'], "primary_group_id");

// Update title for these users

foreach ($users as $user_id => $user){

$user->title = $post['title'];

$user->store();

}

// Give us a nice success message

$ms->addMessageTranslated("success", "Everyone's title has been updated to {{title}}!", $post);

}

{% endraw %}Submitting the Form

Ok, so remember how I mentioned earlier that there are two different ways that we can submit the form? Well, I did.

One option is to use a traditional form submission (i.e., just creating a submit button and letting HTML handle the rest). If we do this, most browsers will take the response from the POST request and display it in the browser, just like they do with any other request. In this case we'd probably want to redirect the browser back to the submitting page, or perhaps a confirmation page, since the response body from the POST request itself will be empty (and we'd just get a blank page).

However, we could choose to use AJAX instead. This is actually how most of the forms that ship with UserFrosting already work. In this case, Javascript will detect when someone submits the form, and will pass the data to the POST route without leaving your current page. In this case, there is no need to redirect to another page (and actually, this wouldn't work because the response of that redirect would be sent back into the AJAX callback). Then, if necessary, we can use Javascript to reload the page after the request to the POST route is complete.

The other nice thing about using AJAX is that, before the form is actually submitted, we can validate the contents of the fields with a Javascript plugin. This does not mean that we don't have to validate the data in the POST route as well - it simply makes things a little easier on the client by telling them immediately if their input contains an error. This way, they don't have to wait for the round trip to the server and back.

To have the form submitted via AJAX, add this block of Javascript code immediately before your closing </body> tag in the page template:

{% raw %}

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

// Process form

$("form[name='titles']").formValidation({

framework: 'bootstrap',

// Feedback icons

icon: {

valid: 'fa fa-check',

invalid: 'fa fa-times',

validating: 'fa fa-refresh'

},

fields: {{ validators | raw }}

}).on('success.form.fv', function(e) {

// Prevent double form submission

e.preventDefault();

// Get the form instance

var form = $(e.target);

// Serialize and post to the backend script in ajax mode

var serializedData = form.find('input, textarea, select').not(':checkbox').serialize();

// Get unchecked checkbox values, set them to 0

form.find('input[type=checkbox]').each(function() {

if ($(this).is(':checked'))

serializedData += "&" + encodeURIComponent(this.name) + "=1";

else

serializedData += "&" + encodeURIComponent(this.name) + "=0";

});

var url = form.attr('action');

return $.ajax({

type: "POST",

url: url,

data: serializedData

}).done(function(data, statusText, jqXHR) {

// Reload the page

window.location.reload();

}).fail(function(jqXHR) {

if (site['debug'] == true) {

document.body.innerHTML = jqXHR.responseText;

} else {

console.log("Error (" + jqXHR.status + "): " + jqXHR.responseText );

}

}).always(function(data, statusText, jqXHR){

// Display messages

$('#userfrosting-alerts').flashAlerts().done(function() {

// Re-enable submit button

form.data('formValidation').disableSubmitButtons(false);

});

});

});

});

</script>

{% endraw %}Ok, so what's going on here? $(document).ready(... is a jQuery construct that tells us to execute the enclosed code when the HTML document is ready (i.e., the page has completely loaded).

$("form[name='titles']").formValidation(... creates a new instance of the FormValidation plugin, which will perform our client-side validation. The line fields: {{ validators | raw }} is where Twig will insert the client-side validation rules that it generates from the schema (more on this in a minute).

e.preventDefault() overrides the default form submission behavior, letting AJAX take control instead. We then serialize all the form data into a URI-encoded string, and pass it into a call to $.ajax(..., which actually performs the submission.

The AJAX construct includes three callbacks: .done, .fail, and .always. .done is called when the POST request is submitted successfully, i.e. when it returns a HTTP 200 response code. In this case, we may want to reload the page using window.location.reload() (the necessity of this will depend on your specific application).

.fail is called when the POST request returns an HTTP code other than 200, for example 400, 403, or 500. In this case, we may want to take the client to a debugging page, or simply log the error code in the browser console.

.always is called regardless of whether the request was successful or not. We always want to display any messages from the message stream, using UserFrosting's flashAlerts() jQuery plugin. This will take care of displaying both success and error messages.

Client-side Validation

Ok, so about that client-side validation. We already have a Twig placeholder, we just need to generate the appropriate rules as a JSON object. It turns out that Fortress can do this as well, we simply need to load the RequestSchema in the page route:

{% raw %}

public function pageGroupTitles(){

// Access-controlled resource

if (!$this->_app->user->checkAccess('uri_group_titles')){

$this->_app->notFound();

}

// Get the validation rules for the form on this page

$schema = new \Fortress\RequestSchema($this->_app->config('schema.path') . "/forms/group-titles.json");

$validators = new \Fortress\ClientSideValidator($schema, $this->_app->translator);

// Get a list of all groups

$groups = GroupLoader::fetchAll();

$this->_app->render('group-titles.html', [

'page' => [

'author' => $this->_app->site->author,

'title' => "Update Group Titles",

'description' => "Update the title for every user in a particular group",

'alerts' => $this->_app->alerts->getAndClearMessages()

],

"groups" => $groups,

"validators" => $validators->formValidationRulesJson()

]);

}

{% endraw %}We generate a new ClientSideValidator object from the request schema, and then use the formValidationRulesJson() method to generate the client-side validation rules in the appropriate format for the FormValidation jQuery plugin. These then get passed into the page template.

Wrapping it up

Alright, so that should do it! To summarize, we created the following:

- A

GETroute and controller method to generate the page that will contain the form. - A

POSTroute and controller method to process the form submission and modify the data model accordingly. - A WDVSS schema to facilitate both server- and client-side validation of user input.

If we go back to our page and fill out the form, we should get something like: